‘Let’s go to Lake Vyrnwy,’ Husband said. ‘Take some photos.‘

“Take some photos”, is a phrase that has been used many time down the years of our marriage. Sometimes it makes my heart sink; it often means I carry on walking along a chosen trail, before realising I’ve left Husband behind, oblivious, and capturing, “just the right shot” and have to retrace my steps. I have complained that this means I have walked miles more than him, but he, (“quite reasonably,” he says) means I’m burning more calories off. I ignore the implication of this… normally… but make sure I eat his chocolate bar as well as my own, when we stop for lunch.

Anyway… Lake Vyrnwy...

Just on the edge of The Snowdonia National Park and south of Lake Bala, Lake Vyrnwy is set amidst the remote and beautiful Berwyn Mountains. With spectacular waterfalls, and unspoilt open countryside. Except that, although the scenery is, as always, fantastic, the waterfalls are sadly depleted. As is the reservoir. However, since these photos were taken in August, and we’ve had such downpours, with fingers crossed, an inch or two may have been added to the water level. One can but hope!

We parked in a designated area that was supposed to be on the edge of the lake. It wasn’t; the water was so low we could have walked quite a few metres on shingle that should… would … in ‘normal times’ be submerged. It reminded us that, underneath, was a village, lost many years ago.

Llanwddyn was a village on the hillside next to the Cedig river. There were thirty-seven houses, three chapels and a Church of St John, and, in the surrounding countryside, ten farmsteads. Farming was the main occupation of the people in the valley, they ate simple food, such as mutton broth, porridge, gruel, and milk and burned peat from the moors in their fireplaces.

But, with expanding industries in the the Midlands and the north-west of England, and the prospect of higher wages, many people left. To make matters worse for those still trying to make a living from the land, in 1873 the local vicar,Reverend Thomas H. Evans published a report that the area was useless for agriculture, because it was waterlogged for much of the winter.

Seeing this, made us realise how many streams must has poured down the hills. Imaging the rush of water, I suppose it’s easy to understand the Reverend’s statement. Yet it has left me wondering why he wrote the report. Was he paid? Were the villagers aware of what he’d done? If they did find out, what was the reaction? I haven’t been able to discover that. The writer in me is itching to research that time. It did coincide with a time when the authorities of Liverpool were exploring the country for sites to build a new reservoir to cope with the growing population on both sides of the Mersey. So who’s to say!

Various sites were under consideration in northern England and Wales, but in most cases there were snags By 1877 a group of engineers arrived in Llanwddyn. Their visit was to look into the possibility of damming the river Vyrnwy. A survey revealed a large area of solid rock, just where the valley narrowed, two miles south of the village, which could act as a base for creating a large, artificial lake that had the potential for holding many millions of gallons of water.

It brings a feeling of awe, of sadness, almost, to be walking on land that is normally submerged under water, on land where a village once stood, where people once lived.

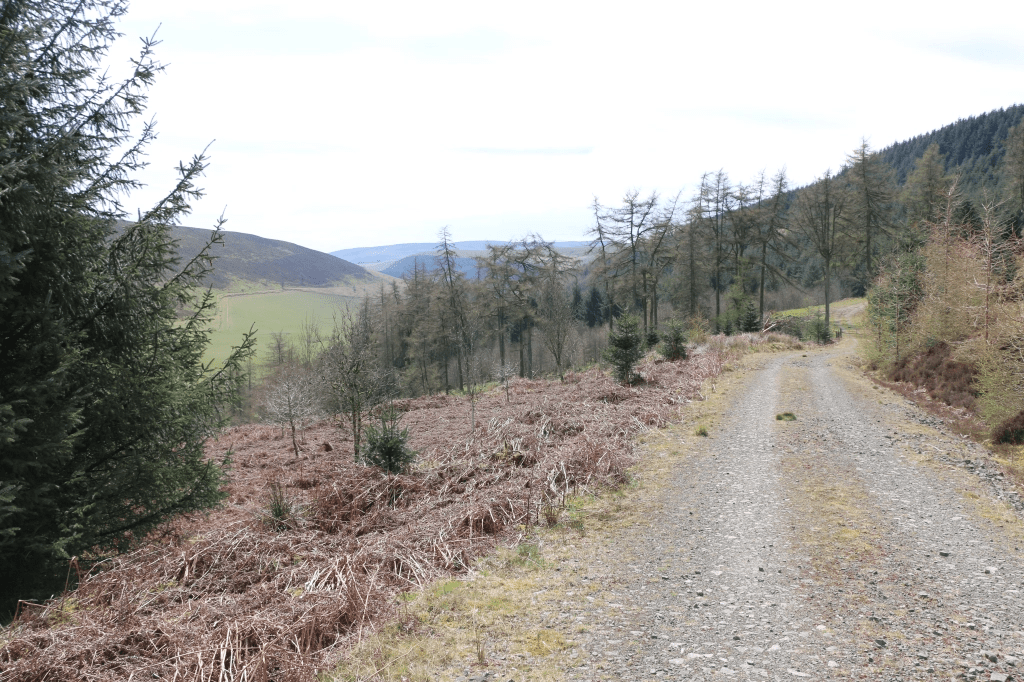

Driving further around the lake we pass a sign at the side of the road – “Track to impressive hillside view. Not to be missed”. Well, if ever there was a challenge to a photographer, that was it. Husband got out of the car and disappeared for a few minutes, soon to return. ‘It doesn’t look too bad. Come on.’

And indeed the first few steps were not too bad. And then we turned a corner… to be faced by an almost vertical path, a rocky vertical path. I stopped; why do I always let myself be fooled?

‘Come on, it’s not far!’ He said that numerous times for the next ten minutes. Hauling me from bend to bend. ” Think of the view!”

I couldn’t think of anything, except how to get my next breath.

But I had to admit, the view was worth it. The coniferous forests planted around the lake by the Forestry Commission are impressive.

On the way back, Husband found two stout branches to use as walking sticks, to scrabble down between mossy rocks and sliding muddy stones. It was either that or an undignified descent on my backside.

In 1880 the Liverpool Corporation Waterworks Act was passed by Parliament, and received the Royal Assent. Preparations were at once put in hand to gather the work-force and equipment necessary for the construction of what was to become the first large masonry dam in Britain and the largest artificial reservoir in Europe at the time. Work on the site began in July 1881.

The stone for the masonry was obtained from the quarry specially opened. All other materials were brought by horse and cart from the railway station at Llanfyllin, ten miles away. Stabling for up to 100 horses was built in Llanfyllin. The labour force topped 1,000 men at the busiest stage of the work on the dam. Many of them were stone masons working in the quarry, dressing the stone which was not easy to handle.

In a very short time the dam was completed. The village of Llanwddyn, and all buildings in the valley that were designated to be covered by the water, were demolished.

©Martin Edwards

St Wddyn’s church was built on the hill on the north side to replace the parish destroyed by the flooding of Vyrnwy valley. Many of the graves were relocated from the graveyard of the old church to St Wddyn’s before it was flooded. It was was consecrated on the 27 November 1888, the day before the valves were closed. It took a year before the water reached and spilled over the lip of the dam.

On a previous walk, some years before, we witnessed a wedding procession coming from the church, led by a chimney sweep in all his glory. Apparently it’s considered lucky to see a chimney sweep on your wedding day, the belief being they bring good luck, wealth, and happiness. The bride and groom did look joyous. I would have loved to have tagged onto the procession, but, that day, we were looking for “a good view of the water”, further along the road.

On the same hill as the church a monument was erected in memory of ten men who died in accidents on the site during the building of the dam and another thirty-four who died from other causes at the time.

Stone houses, matching the stone of the dam, were built on either side of the valley for the people whose homes had disappeared under the lake. I suppose there must have been a lot of opposition to flooding the valley to provide Liverpool with water at the time, and since, but records have apparently shown that it brought prosperity and stability to the area.

Our final excursion on our walk was to the waterfalls.

One of the highest is the Rhiwargor waterfall at the northern end of Lake Vyrnwy. From the car park I was relieved to see the relatively flat path along the valley of the river Eiddew. There was a trail leading up and up along the side of the falls. Despite much attempted persuasions, I declined, and opted for a coffee and a picnic at a nearby picnic table. And I ate his chocolate bar! Well, after that impromptu climb earlier, I thought I deserved it. Who said I hold grudges?!!

N.B. The Lake Vyrnwy Nature Reserve and Estate that surrounds the lake is jointly managed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and the Hafren Dyfrdwy (Severn Dee). The reserve is designated as a national nature reserve, a Site of Special Scientific Interest, a Special Protection Area, and a Special Area of Conservation.