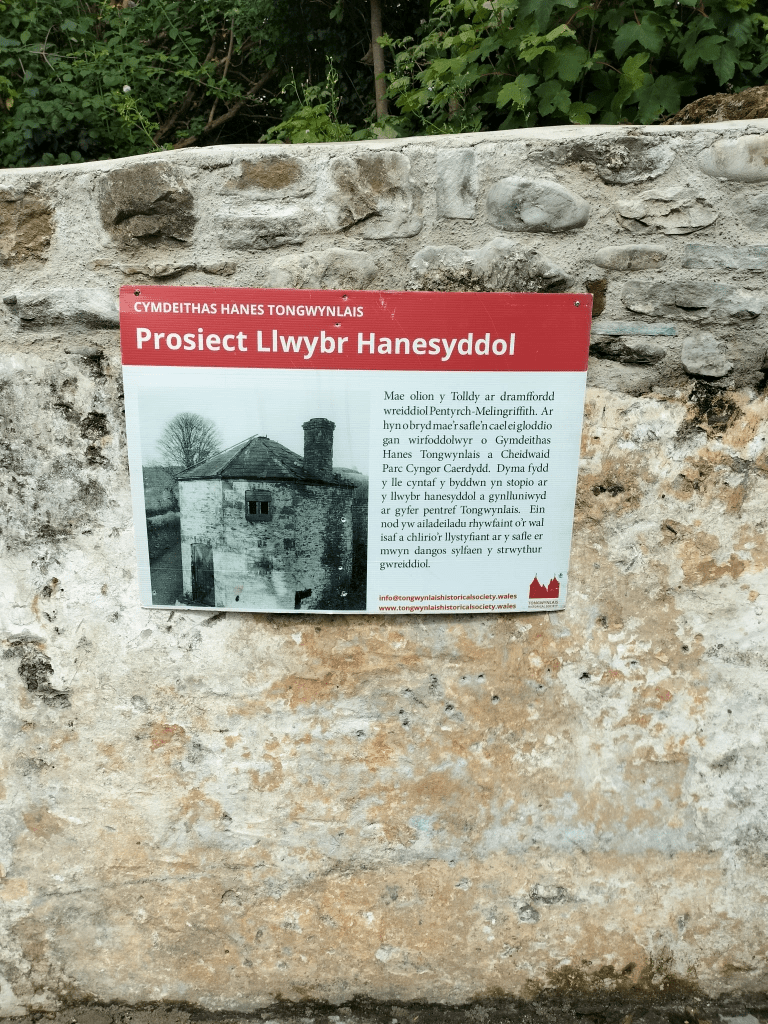

An update to my post: Tongwynlais: Historic tollhouse given new lease of life:https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-62718289

Edmundo Ferreira-Rocha, of Cardiff council’s Urban Park Rangers, and councillor Linda Morgan cut the ribbon at the opening ceremony. © Tongwynlais Historical Society.

© Tongwynlais Historical Society.

“Villagers have restored the shell of a historic “unloved eyesore” tollhouse demolished more than 70 years ago. The original building was among hundreds used to collect money from 18th and 19th century travellers. Volunteers in Tongwynlais, on the edge of Cardiff, have spent more than a year rebuilding it as the first step towards creating a local history trail. “Our volunteers have been fantastic,” said Sarah Barnes, of the Tongwynlais Historical Society.

*******************************************************************************************************

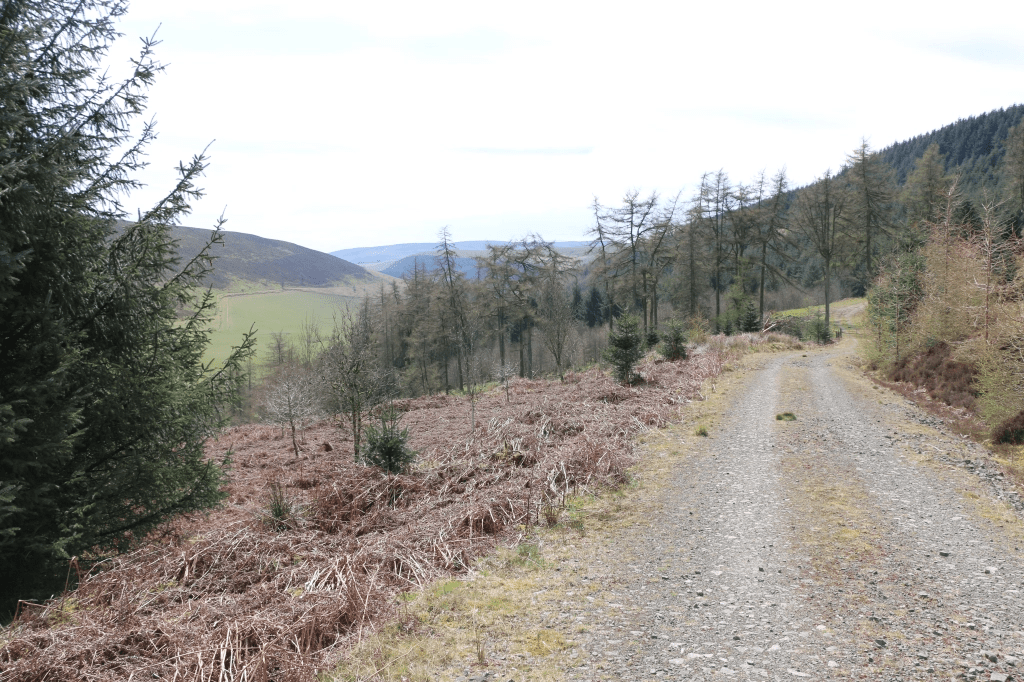

Before this wonderful restoration granddaughter and I walked the Taff Trail – so thought you might like to see the before and after. Or, in the case of this blog, the “after and before”.

Put a lovely sunny day, with a dog desperate to go a walk, with a granddaughter who needs to be dragged from her mobile and bribed by the thought of a chocolate brownie and a drink of Sprite, and there was only one place to head for, the cafe in the garden centre at the end of the Taff Trail in Radyr.

The Radyr section of this lovely river walk is one we’ve done often

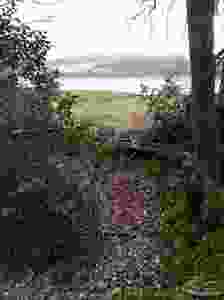

But this time we decided to meander along various smaller paths, even though we needed to retrace our steps numerous times. I was so glad we did because look what we found:

The tollhouse, once used by the Pentyrch and Melingriffith Iron and Tinplate Works in the late 1800s

I thought I’d better seek permission to add some of the photographs from the Tongwynlais Historical Society. I made contact with a very helpful chap, Jack Davies, whose fascinating website also contains an article about the Tollhouse and other history of the village: https://tongwynlais.com/history/

Seren also very kindly leant a hand to point out this lovely heart shaped stone, with a wonderful inscription:

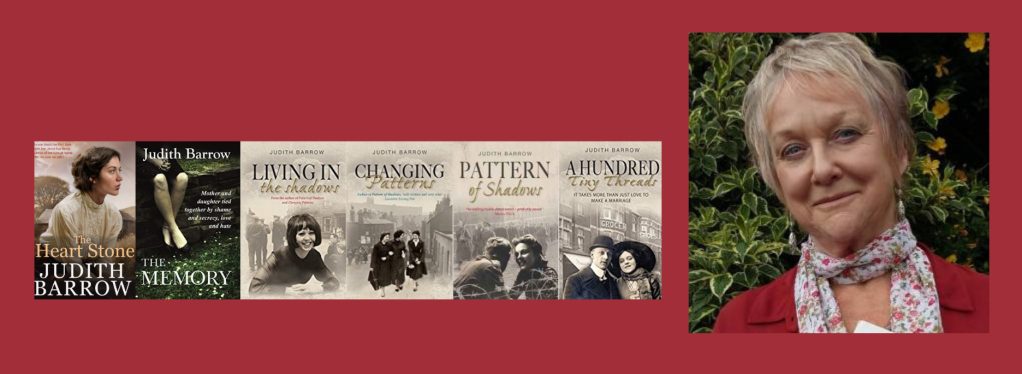

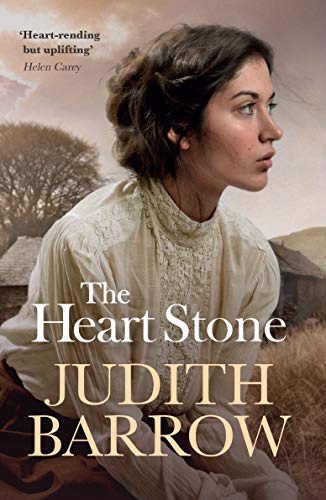

Which immediately brought to mind (well, my mind anyway), my book, The Heart Stone, which was published by Honno, in 2021: So, never one to pass up on an opportunity…

The inspiration for The Heart Stone partly came from research for my degree on The First World War some years ago; a subject that both fascinates and repulses me. At the time I’d found my grandfather’s army records and discovered he’d volunteered to join the local Pals Battalion with two of his friends, although they were all underage.

I only ever remember him as a small man who spent his days in a single bed under the window in the parlour, who coughed a lot, and was very grumpy. He died when I was eight.

There was no conscription at the beginning of the war. The Pals Battalions were formed, to answer Lord Kitchener’s call for volunteers, by encouraging local magistrates to drum up community spirit and patriotic fervour.

The gist of the speeches used were that young men,”… should form a battalion of pals, a battalion in which friends will fight shoulder to shoulder for the honour of Britain and the credit of their town and villages.”

My grandfather was gassed in 1916 near the Somme. He was also shell-shocked and was unemployed for the rest of his life. Once, my mother told me he had never spoken of his experience but had suffered nightmares for as long as she could remember. And that there were whole streets around the house where they’d lived where the men had never returned.

It’s a haunting image.

Four years ago, after my mother passed away and we were clearing her home, I found my grandfather’s army papers again.

During the following week, whilst my husband and I were walking along the Pembrokeshire coastal path, we found a smooth stone, almost heart shaped, placed on top of a cairn amongst the Marram grass. Picking up the stone to examine it, a folded paper blew from underneath. There had been words on it but were, by then, indecipherable.

A love note, I thought; a love note under a heart shaped stone.

A love note, under a heart shaped stone, from a young man who had never returned.

And so The Heart Stone started to form.

The Heart Stone was published by Honno Press in Feb 2021

And a Review of The Heart Stone:

And a buying link:

Amazon.co.uk: https://amzn.to/3hupbc1

Also available from Honno

And a little bit about me:

I’m,originally from Saddleworth, a group of villages on the edge of the Pennines, but have lived in Pembrokeshire, Wales, for over forty years.

I have an MA in Creative Writing with the University of Wales Trinity St David’s College, Carmarthen. BA (Hons) in Literature with the Open University, a Diploma in Drama from Swansea University. I’m also is a Creative Writing tutor and hold workshops on all genres.

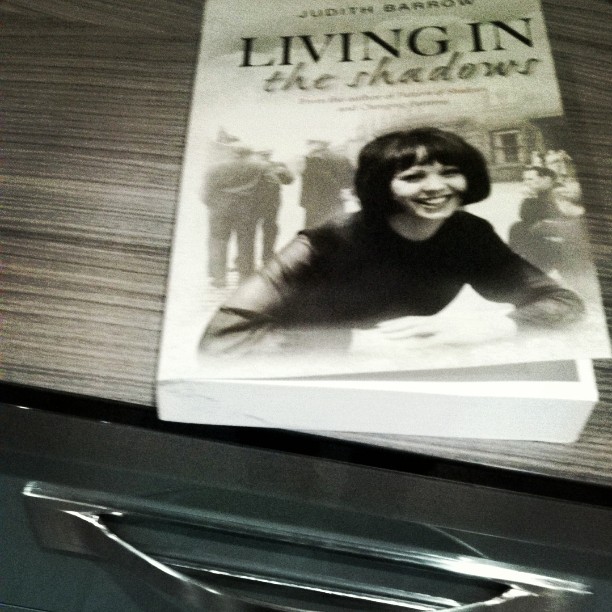

And here I am:

https://twitter.com/judithbarrow77

https://www.facebook.com/judith.barrow.

![Women of Britain say GO [image credit: E J Kealey (artist) Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (copyright owner/commissioner) Hill, Siffken & Co. (L.P.A. Ltd.) (Publisher) Adam Cuerden (Restoration) - Te Papa Tongarewa (The Museum of New Zealand)] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_hall#/media/File:Women_of_Britain_Say_-_%22Go%22_-_World_War_I_British_poster_by_the_Parliamentary_Recruiting_Committee,_art_by_E_J_Kealey_(Restoration).jpg](https://judithbarrowblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/women_of_britain_say_-_-go-_-_world_war_i_british_poster_by_the_parliamentary_recruiting_committee_art_by_e_j_kealey_restoration.jpg)

Goodreads Synopsis:

Goodreads Synopsis: